In May 2020, facing mounting criticism from privacy advocates, Sidewalk Labs CEO Daniel Doctoroff announced that the Google-backed company was scrapping its smart city project in the Quayside neighborhood of Toronto. With its passing, there was a sense among critics that some sort of evil had been defeated—that the little guy had won and Alphabet/Google had been routed. When Sidewalk formally discontinued its parallel Portland, Oregon, project earlier this year, the response was similarly jubilant, if more subdued.

In the aftermath, Sidewalk itself appears to have gone to ground, quietly patenting out some of its bespoke technologies. Likewise, the smart city dream it piloted looks to be dead as a doornail, now that Waterfront Toronto (Sidewalk’s erstwhile governmental collaborator for Quayside) is actively shopping around for a new development partner. Hopefuls will jostle in an international competition that compels proposals to take “into consideration the experiences of 2020, including the COVID-19 pandemic, growing social inequality, economic insecurity and mounting climate crisis.”

It’s easy to read the new Quayside competition criteria as a direct rebuke of the virtues espoused by Sidewalk Labs’ bid. Nearly all mentions of smart technologies have been scrubbed, replaced by an ethos of community, inclusivity, and resilience. The vestiges that do remain, such as an interest in mass timber construction and, funnily enough, Sidewalk’s own dynamic storefront proposal called Stoa, have been pressed into the service of a “people-centered vision,” as The Guardian put it. (That the news outlet could make such a value judgment in the absence of any definitive project materials is telling.)

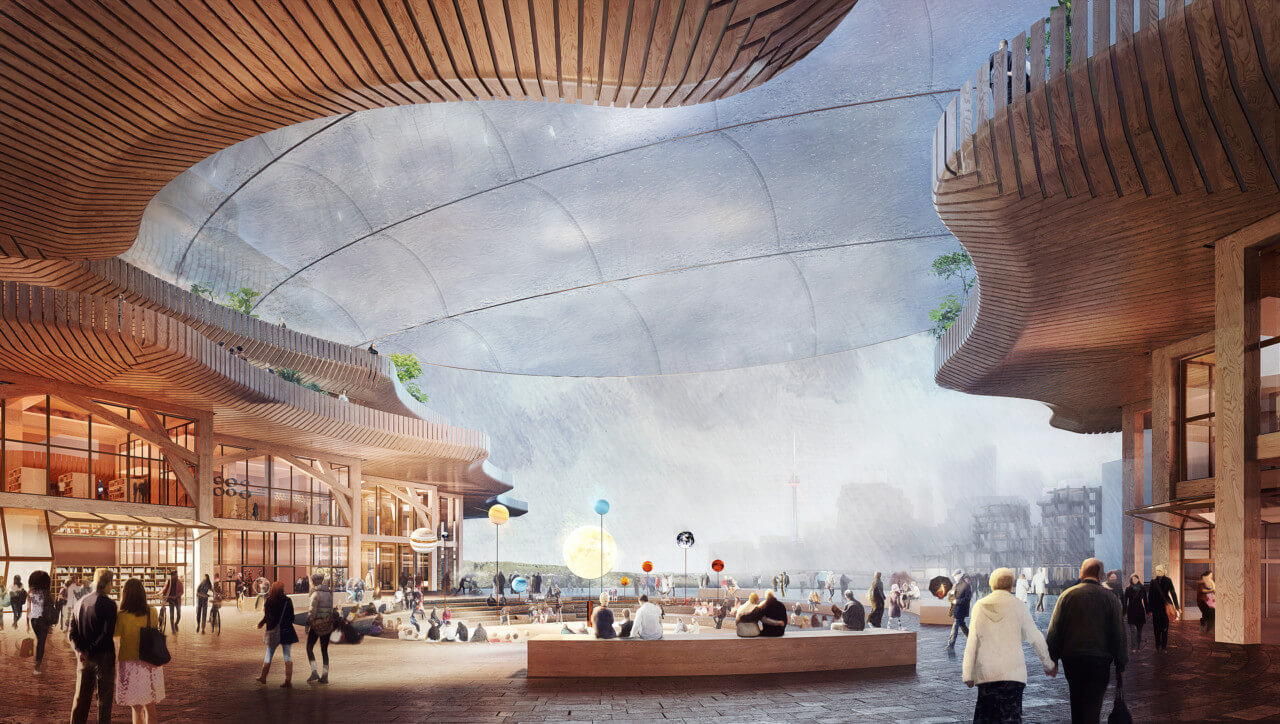

Yet in celebrating the demise of Sidewalk Toronto and its replacement by Waterfront Toronto, activists and journalists alike have misread the situation. The former Quayside project, imagined as a timber arcadia designed by Snøhetta and Heatherwick Studio, was never the official avatar of the smart city but a relative outlier. Its aims were unlike those of the real smart city, which, far from being defeated, remains in its infancy.

All along, Sidewalk Labs presented its project as an urban innovation beginning and ending in space, but this is a fundamental misdirection. The spatial component of any given smart city—Quayside or otherwise—is only the visible eye of a vast leviathan; were one to manage to blind it, it would continue unabated in its grim work.

Still, this beast is boring. All the flashy renderings, scintillating buzzwords, and exhibition-ready prototypes are there to obscure the smart city’s true function as a bog-standard development guide. As a 2017 Bloomberg Smart Cities panel asserted, the overarching goal of smart city projects is not one of techno-imbued construction but of “leveraging creative models of financing and public-private partnerships to navigate financial barriers and help achieve infrastructure improvement goals.” This is a far cry from the heroic vision peddled by Sidewalk. Consider that the bulk of the company’s research and proposals entailed radical re-imaginings of existing urban infrastructure, from roads to buildings; consider also the promises of urban dashboards and responsive environments pitched to prospective residents. Altogether, Quayside was an attempt to position the smart city as a gussied-up lifestyle product on offer to the striver class. Meanwhile, in the hushed back rooms of the public-private urban regime, the smart city evokes any number of interrelated optimization or austerity projects.

That is to say, the real power and money to be made in the smart city market lies not with the relatively local and easily lambasted technological futurity of Sidewalk Labs or, more recently, Toyota’s flamboyant Woven City in Japan, but in think tanks, trade publications, mayors’ consortia, university programs, and post-COVID reset conferences. Realizing a fully furnished “test bed” urbanism along the lines of the BIG-designed Woven City (construction on which is said to have broken ground this past winter) pales in comparison with the prospect of universalization—i.e., the reduction of existing cities to pure quantification up until the point any may be assessed alongside any other. The goal, then, is to reconceive cities and “cityness” as an economistic array of parseable criteria, development targets, and smartness rankings that ultimately determine the availability of funding and willingness of potential investors.

The Eden Strategy Institute and other industry watchers indicates as much when it asserts that smart cities have entered a new phase, dubbed Cities 4.0, thereby heralding a shift in focus from technology qua technology to people. The 20-odd locales that have earned the designation thus far all pursue a myriad of smart city projects (an average of 14!), invest in better infrastructure, have incorporated insights from the pandemic into planning models, and hew closely to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The “Resident 4.0” percolating within the City 4.0’s sensible and ecofriendly transit hubs, parks, co-working spaces, and so on is likewise a model employee equipped with “smart skills” who takes advantage of talent-learning opportunities and an appropriate amount of cosmopolitan life (work schedule permitting).

Outside this retinue of smart city projects, nearly all of them in the Global North, smartness is deployed everywhere else according to long-standing developmentalist lines. For all their popularity among policy wonks, SDGs reenact the same classic play of dangling the developmental carrot on the end of the political-economic stick. (The UN and World Bank continue to act out their classic parts, no less.) However, the shrinking of scale from developed/undeveloped nation to developed/undeveloped city deepens uneven patterns of development. Take, for example, Medellín, Colombia, which publications such as Newsweek and Foreign Policy and countless white papers have celebrated as a “city of innovation.” Foreign Policy points to the Metrocable gondola as a sign of the times, claiming that Medellín, a place hobbled by a century of civil war and drug trading, now radiates the glow of smart, innovative policy. Which raises the question, does all contemporary urban development equal “smartness”? And should an improvement in a city’s fortunes automatically bestow upon its mayor or municipal cabal the status of genius, as happened in Medellín?

But never mind the geniuses—the heroic age of the smart city ended with the death of Sidewalk Toronto. This in itself means little, least of all a victory. The smart city has never been “object-oriented,” so to speak, but an ethos founded in the idea that politics itself behaves according to scientific principles of development (or technology). Even as smart city principles take root everywhere—not just in Toronto or Tallinn but in Columbus, Ohio, and Erie, Pennsylvania—they amount to little more than standard environmental improvement programs, such as the installation of traffic cameras or roadwork. The charismatic selling points of smartness—autonomous cars being the paradigmatic example—are nearly always either a fool’s errand or, as in the case of Columbus, the first element of a smart city project to be discarded.

And yet smartness already defines the world: in it is a new watchword for governance, for policy, for austerity, and most of all for economic growth. It has, perhaps most insidiously, been bolstered by its capture of a coterie of self-styled progressives (YIMBYs, eco-urban types, 15-minute-city acolytes, etc.) who believe the invasion of capital into urban space is the only way to build a more “inclusive” city. All are united under the banner of development as capital prosecutes yet another back-to-the-city movement in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Those of us seeking actual, substantive change—activists, radicals, and, yes, even critics—must change tactics, lest we be labeled incurable naysayers. Our critique must first and foremost contend with smartness as a new phase of capitalist development.

Because there are no isolated smart projects. It is useless to discuss them as such, or as the actions of particularly aberrant bad actors applying this or that bad technology or policy. Combating the smart worldview first requires the development of an equally holistic view of the world or else resigning ourselves to, at best, win certain battles while having already lost the war.

Kevin Rogan is a writer, designer, student, and dilettante who lives in New York.