Architectural designer Jennifer Bonner and engineer Hanif Kara have a beef with mass timber, or, rather, the singular meaning its proponents ascribe to the term. The sustainability benefits of engineered wood products like cross-laminated timber (CLT) have overtaken the discourse around them, the duo finds. Manufacturers have an overwhelming influence on the design of timber buildings, many of which simply substitute structural wood for steel. As they spell out in their forthcoming book, Blank: Speculations on CLT (AR+D Publishing), Bonner and Kara fear that if architects relinquish mass timber to the control of industry, they will miss an opportunity to create a new architecture capable of meeting the exigencies of the 21st century.

But Bonner and Kara aren’t dour prognosticators. In the spring of 2020, they organized a mass timber studio at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) around a single element, the so-called blank. They instructed their students to use this blank—a structural sheet comprising three- to seven-ply CLT panels that measured 9 feet long and 50 feet wide—toward experimental ends. And the students heartily complied, fashioning trendy villas and topsy-turvy high-rises out of the stuff. These materials are the focus of part of the new book, which also includes speculative essays that explore the blank’s various facets (and the various facets of “blankness”).

AN’s executive editor, Samuel Medina, caught up with Bonner and Kara to discuss the project as well as their thoughts on the “complex” building up around mass timber.

The Architect’s Newspaper: Why did you want to move away from the broad signifier “mass timber” to something as specific as the blank? What discursive trappings of mass timber—or even those of CLT—were you keen to avoid?

Jennifer Bonner: “Mass timber” is such a big category. It’s just like saying “concrete.” What we wanted to do instead was to be very narrow in our approach by looking at the CLT blank. And that by limiting ourselves to the blank we would be able to conceptualize and theorize its potential beyond the sustainability narrative that dominates mass timber more generally.

Hanif Kara: Without being anti what’s going on [in mass timber], I think that whenever a new material is introduced there is always a “conspiracy” that forms around it with respect to the challenges of the time. When you look at other innovative materials of the past, what you will see is a rush on the part of certain industry players to direct that material toward one end only. This is the conspiracy, and it effectively excludes nonindustry players and innovators as well as opportunities to intellectualize that material. This has been the situation of mass timber until very recently. Because the challenge of our time is undoubtedly about [building] green, mass timber has been driven toward one end—carbon absorption. Of course, this is a very positive thing. But now that the full [applications and potentials] of mass timber are coming to the fore, we are seeing players of all kinds begin to come out of the woodwork. Excuse the English pun.

What was it that drew you to CLT rather than other competing engineered wood products?

HK: When you go to cross-laminated timber, you can see that there is more to it—and more of it—compared to, say, glulam and other things. It also has more credibility than these other [products] do, because it is from juvenile trees and forests. But I had also seen what Jennifer was able to do with CLT at Haus Gables [her 2018 residential project in Atlanta], which AKT II [Kara’s engineering firm] was involved in. As an engineer who has worked with just about every material, I was deeply interested in getting engaged with the way Jennifer’s generation thinks about CLT, which I would describe as being “risky.” Jennifer and I continued to talk after Haus Gables was designed and built. We felt very strongly that we needed to apply a different lens, and that is what we have done with the studio and now the book. By applying this lens—the lens of the blank—we found we could open up a very risky attitude toward design.

JB: Hanif was always saying that there is a danger of losing design to the sustainability narrative. He was always pushing the design questions to the center.

HK: Because if you don’t bring these questions to the broader design [community] like the way we talk about it, then engineers and industry will take over. And if that happens, we’ll never really see any architecture out of it.

It’s important to underscore that you’re not denying the potential of mass timber to advance an alternative paradigm for construction, even if it isn’t quite the guilt-free paradigm some would make out.

HK: Yes, we’re all for it. People are right to connect CLT to the concept of the circular economy, because of its capacity to absorb carbon and be easily recycled. And, as is shown in Norway and Sweden, it can go hand in hand with sustainable harvesting and manufacturing practices. It can be prefabricated off-site, and because it’s so lightweight it can be quickly assembled on-site. At Haus Gables, for example, the panels were installed in 14 days using cranes. But as your question alludes to, timber just won’t be able to take over the whole market—not in the way some people would like it to.

In the interest of better establishing the chronology—it was Haus Gables that drew you to CLT first and then the Harvard studio that pushed you toward the blank. What accounted for that narrowing focus?

JB: Hanif and I did Haus Gables a year and a half or so before the studio. With the house, we cut up the blanks into 87 individual panels in order to rationalize the form. In the end, only a few blanks were used in their entirety. So, thinking about it later, I asked Hanif, “What if we start with the blank first and see what kind of architecture that gets us?”

And what kind of architecture is that?

JB: For me, the blank pushes you toward procedures of drawing and cutting. Because it’s a sheet material, there is a ready-made quality to the blank. It also collapses, or flattens, architecture and structure—with the blank we get everything in one!

There’s also an aesthetics of flatness that comes with it. That’s something [English architect] Sam Jacob explores in his essay in the book. Sam’s whole practice, both the design and theory, has been based on the possibilities of flatness, and even though he hasn’t built with CLT before, he absolutely needs to. It’s totally his material. In my own essay, I say that Aldo Rossi would’ve loved CLT—like loved it—because he was all about figures, elevations, blankness. But flatness turns into volume quickly, depending on how you put it together, right? There’s just a lot of potential there.

That’s an interesting exercise—to read a material back into the history of architecture. You can see that in Ultramoderne’s Chicago Horizon pavilion at the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennial, the way it translates a Miesian tectonic to mass timber.

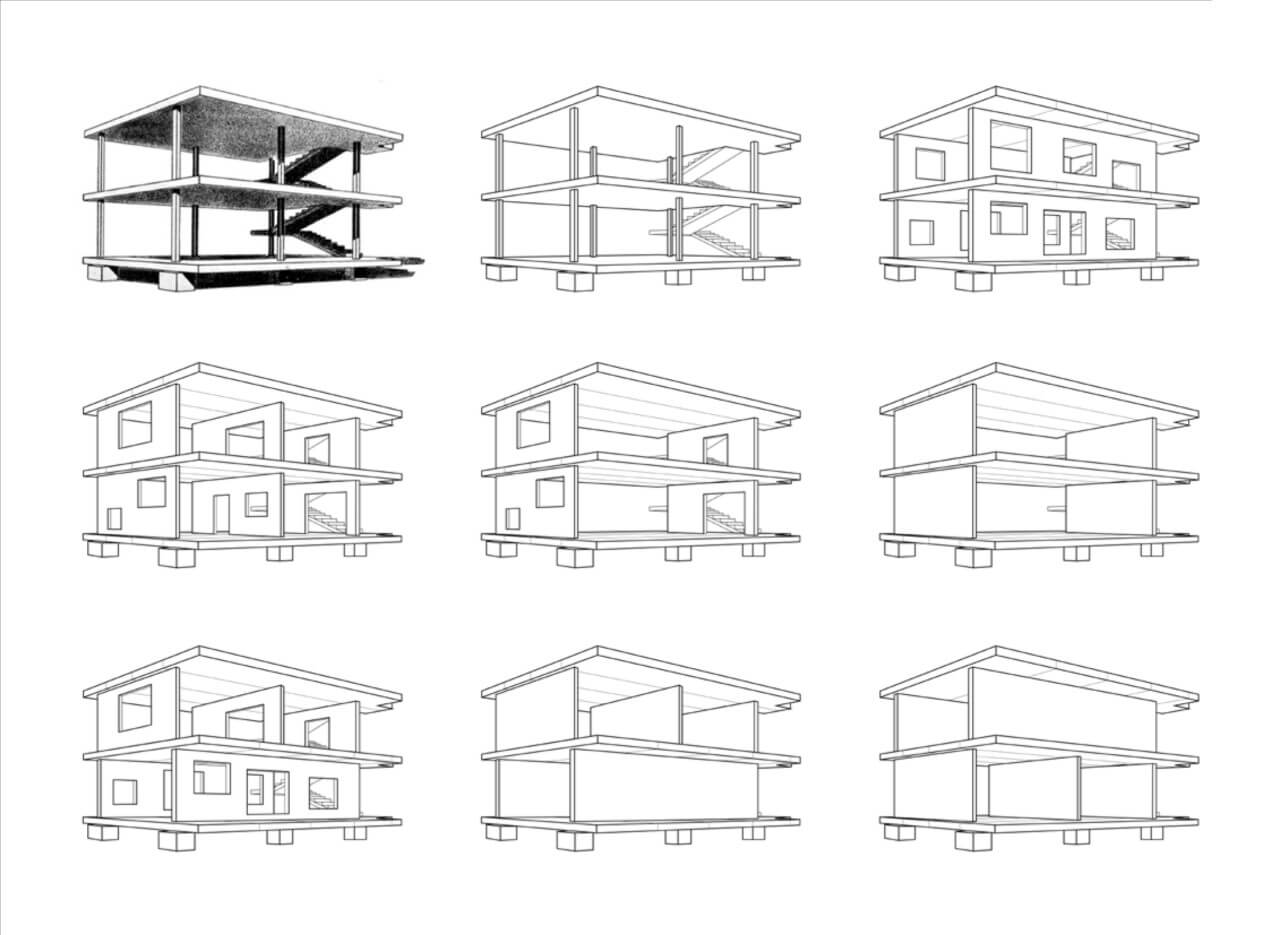

JB: Totally. Funny that you mention that. Hanif created this diagram of the Maison Dom-Ino that illustrates what the blank does. What’s happening in that diagram is we’re deleting the columns and shoving CLT blanks in between the floors.

HK: With that diagram I wanted to start a conversation about the stereotomic versus the tectonic. It’s that classic geometry question—are you carving space or making space? I also meant it as a challenge to the tropes of modernism that certain architects still hold on to, where the skin is freed from the floorplan. But what if you couldn’t free the skin from the structural system (which is what that Dom-Ino diagram is about)? That’s what we didn’t allow our students so that they would ask themselves how they would rethink their architecture. For us, the availability of the blank absolutely forces us to rethink architecture.

Now, the first thing to be said about CLT, structurally, is that it’s not malleable. It can’t be curved easily, because it’s so rigid. It’s not plastic like concrete, which, because it’s so manmade, you can get forensically inside to change its nature. With a blank of CLT, it’s largely a given because it’s so natural. Of course, as soon as you cross-laminate timber, you have interfered with it in the way we do to steel and concrete all the time. Unlike steel or concrete, CLT is the only material that provides weatherproofing, fire resistance, and insulation in a way. It doesn’t cold bridge, where dampness comes through in cold climates or hot climates. It has truly a unique performative capacity.

You’ve just hinted at a few limitations in that description of the blank’s possibilities. What is it the blank can’t do?

HK: I genuinely believe that the lack of malleability is an opportunity rather than a problem, and we were able to show that through the studio work. However, something that the blank doesn’t allow for is double curvature. You know, I worked on Zaha Hadid’s Phaeno Science Center [which opened in 2005] in Wolfsburg, Germany. It was probably the height of the “single surface” idea, where wall becomes floor. There is no such thing as a vertical wall in that building. Everything is either a beam or a hybrid between beam and slab. You wouldn’t believe how much timber [formwork] it took to make that concrete. You just wouldn’t believe it. Before Wolfsburg, the “single surface” would have been something that had surfaces in both directions, where the walls would move on plane. They could rotate from floor to floor. That the blank can do. But it can’t curve in the way Zaha did.

JB: I guess it really does fail in that way, Hanif. [Laughs.]

HK: But the other dimension that is left out is the weight, and that is fundamental. I should do the calculations, but if we had made Haus Gables out of 100-millimeter [4-inch] concrete, it would have probably ended up 10 or 20 times heavier. And you would need metal or timber shutters to form the concrete. You’re right that the blank fails because it can’t achieve what that Zaha project did, but if Zaha Hadid Architects took it on, they could produce something close to that effect using slightly sloped orthogonal blanks. In fact, they are about to start construction on a football stadium in the U.K. entirely made from mass timber.

In a way, Thomas Heatherwick’s [2020] Maggie’s Centre [in Leeds, England] is taking that challenge on. It’s one of the projects we have in the book and one that my firm worked on. It is CLT, but it also wastes a lot of CLT to show how you can do this kind of curvature. Ultimately, that isn’t what we were studying with the studio.

You had your students apply the blank toward drastically different ends. Over the course of a single semester, they each designed a single-family house as well as a multifamily, high-rise tower. How did they take to that challenge?

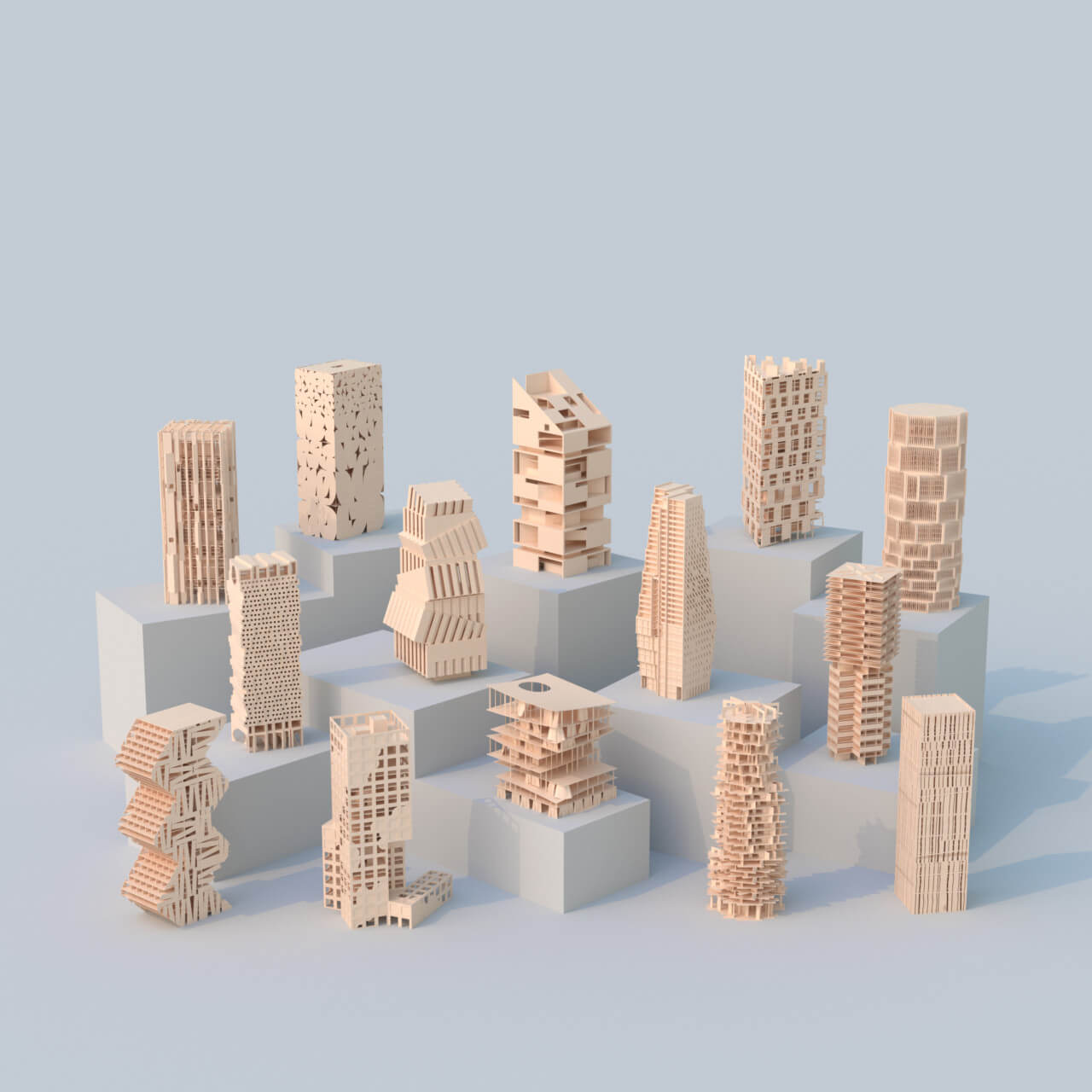

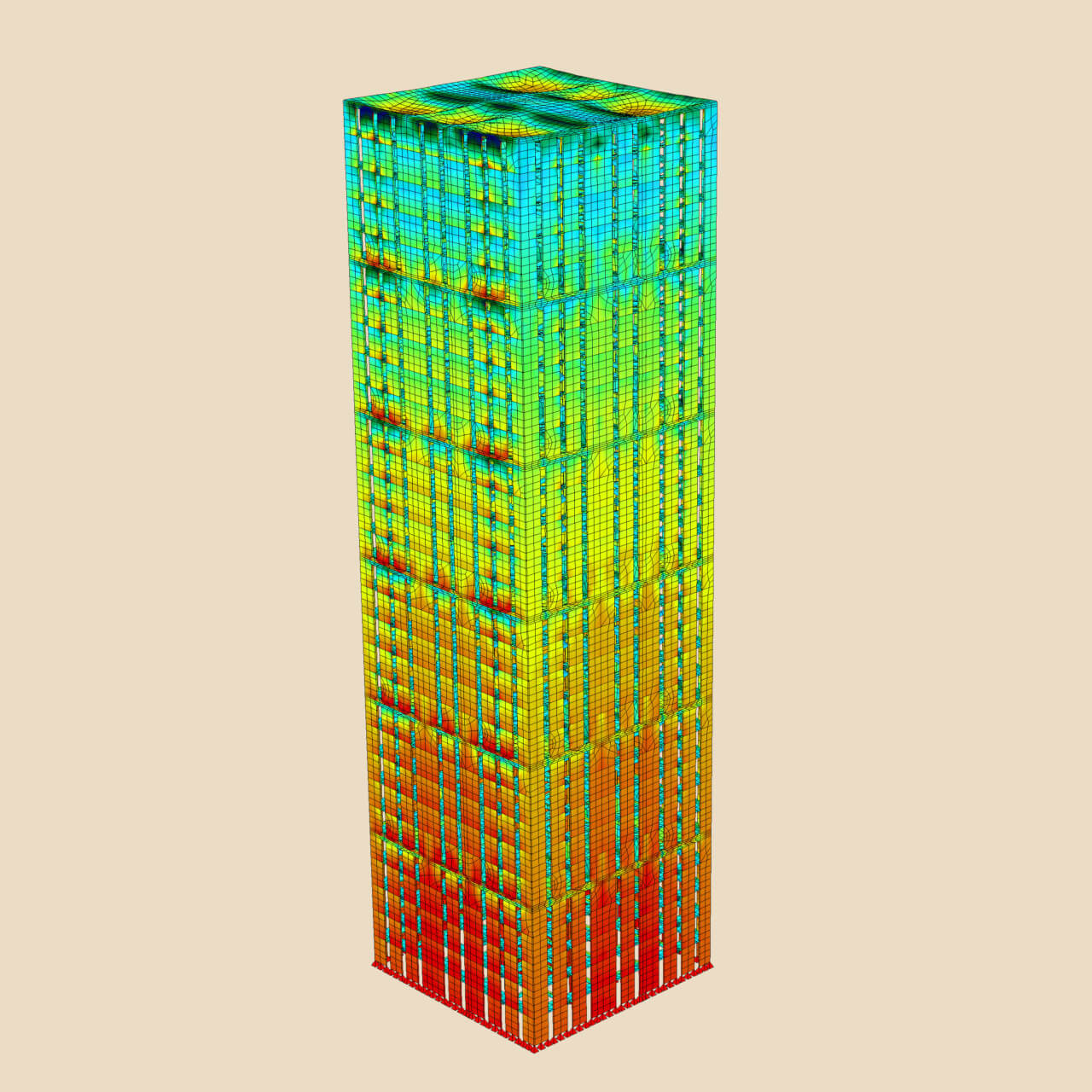

JB: We thought it would be an interesting exercise to have them wrestle with the blank at these different scales. Because that’s the phenomenal thing about the blank: its ability to jump scales. As an architect who had done a CLT house—the first time I had ever worked with mass timber—I of course immediately wanted to [next] go as big as I could. I’m not just the house architect, you know? That’s where having Hanif’s support was so valuable. He and AKT II even ran structural analyses on some of the students’ towers. Without him we wouldn’t have been able to pull it off.

HK: For the tower, we gave the students a [height] limit based on what we know has already been built; with mass timber that upper limit is 70 meters [230 feet]. But we also know that, as with all record breaking, the next version will be 10 or 20 percent taller. So that is what we set the students—an increase of 20 percent, but not 200 percent, because that would have been ludicrous. You just can’t do that with CLT yet. But for the height we had specified, the technology is already there.

The tower assignment was also related to our thinking about the contemporary urban condition. People all over the world are becoming more urbanized. That doesn’t mean every city will become a Dubai or a New York, but it does mean they will all have a need for higher-density buildings. Over here in Europe, CLT is already being used in social housing, not in supertall projects but what we call “mid-rise” projects. We wanted to expose the students to that typology. And by having the tower-versus-house extreme, we avoided the criticism that always comes from these student housing exercises, where they are doing single[-family] houses for five people. We wanted to stimulate the thinking about the blank and its scalability because we know that the two extremes—and everything in between—are up for grabs now.

As with everything else, the studio was impacted by the lockdowns induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. How did the virtual studio setting affect the students’ work?

JB: With every studio there’s a ton of representation, and this one was no different. Part of the brief was forefronting animation and simulations of cranes erecting the towers. We had also planned to have these large-scale models in the studio, all of them made out of wood and which everyone would have loved, but then COVID shut us down. So, when we were planning the book, we had the students rerender their towers against different backdrops. Some of them were really flashy and saturated and others were more neutral, like a Yeezy fashion line, as we put it in the introduction. We also display the “offcuts” of the blanks on the ground, just so that you see how these things are cut up. That’s another kind of representational type we’ve included.

That’s interesting, because in your introduction to the book you speculate on the potential for CLT construction to do away with drawing sets altogether. Were you merely being polemical, or is that potential real?

JB: I’ve never produced drawings like the “offcuts” we have in the book. Typically, I’d hand my model over to the fabricator or manufacturer, who collapses it and starts running their tooling paths for the CNC machine. There was a moment in the 2000s when everybody was showing their nested panel diagram and how all their parts fit on a CNC or laser cutter bed. And we’re aware that these drawings look like those nested drawings, but they’re not. What they’re showing are the blank. There’s nothing nested inside of anything. That’s the full length of the CNC bed. And that these become a kind of figure-ground. But saying that, they are a bit nostalgic because you wouldn’t really ever draw these as an architect. This is all in the machining of the manufacturer now.

HK: It’s an interesting thing because for forever architects have connected drawing to making. When you draw concrete and steel, there’s a particular way to draw it that is very detailed and very element-driven, but nonetheless, it’s abstracted.

But when you draw CLT, it is something like three steps closer to making the building. You are effectively just scaling the drawing up at that point. That is one of the reasons we ran these analyses on the student towers. You can see that if you only made these analyses big enough, you would make the building. You just can’t do that with any other material. What we were trying to show with those stress diagrams was that the material, because it is panelized, allows for redundancy. The real issue, then, is around the joints. Now, there are some people who will say that the connection between drawing and making that the CLT enables is too simple and that in a way we’re going backward. But I like to think that it coordinates itself and, for that reason, we’re moving forward.