Much has been made about the physical separation necessitated by the novel coronavirus. But the pandemic has also laid bare the digital divide separating communities across the country. Over the past few months, millions of Americans have had to shift their daily activities online with the help of web-based applications, productivity tools, and videoconferencing platforms. Everything from concerts to classes, office work to commencement ceremonies, was either canceled or expected to seamlessly transfer to the digital sphere until further notice, making many people more reliant on residential broadband.

This unprecedented surge in traffic has put a strain on our telecommunication infrastructure, especially in underserved communities. While the infinite expanse of cyberspace has made our social circles feel bigger than stay-at-home orders have physically permitted, not everyone has access to affordable high-speed internet or the privilege of working remotely. With even more pandemics of the current sort on the horizon, our ties to society—our interactions with loved ones, employers, teachers, news media, retailers, and even medical professionals—depend on the availability and strength of our internet connections.

The pandemic has also emphasized how internet access is a spatial and material enterprise. For example, mapping is a spatial practice, but the maps used by the Federal Communications Commission to allocate funding for telecom services continually bungle data and misrepresent need, leaving residents in marginalized neighborhoods with few options for broadband. In a sense, these inaccurate maps justify inequity, excusing the lack of investment in places that would clearly benefit from it. The sudden appropriation of neglected urban space in these communities has only served to highlight the below-par connectivity available to them. Parking lots serving schools, libraries, sports arenas, and drive-through restaurants have been transformed into safe zones for people seeking free or fast wi-fi. Additionally, school districts across the country have converted buses into mobile hot spots and issued thousands of tablets to help children without reliable internet complete their homework. This distribution of devices is part of a larger network of digital technologies transferring above-average quantities of information through fiber-optic cables and energy-intensive servers housed in data centers around the world. At the building scale, seemingly tertiary considerations—the placement of a router, the number and proximity of devices, or the type of wall finish—could impact wireless signal propagation and data transmission.

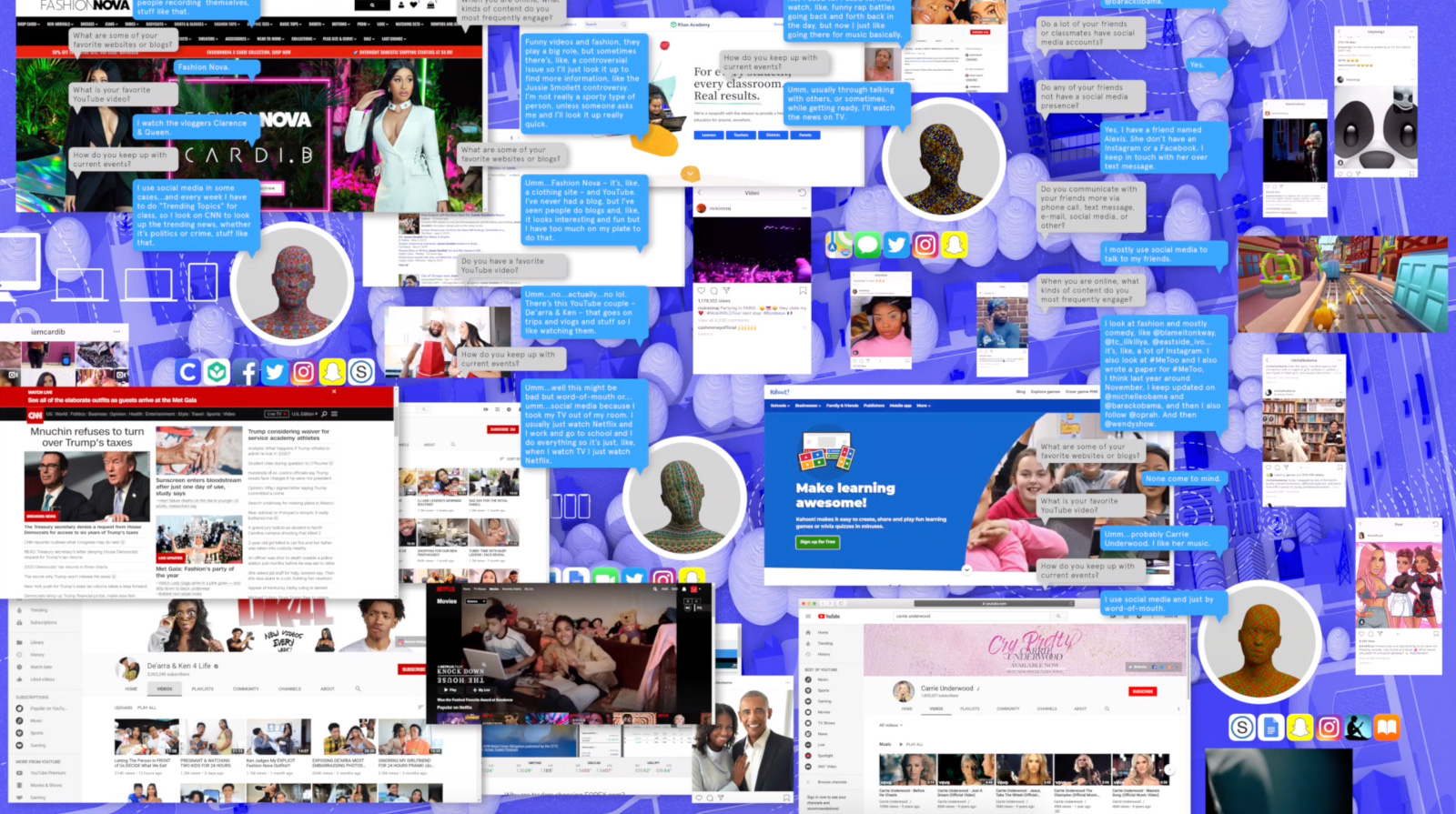

In my practice, EXTENTS, I’ve been investigating how these spatial and material elements can be designed to promote digital equity. Focusing on Detroit, a municipality with one of the lowest rates of internet connectivity in the United States, my work combines publicly available spatial data with local insights—gathered from interviews with government officials, nonprofit organizations, creative professionals, and high school students—in order to map digital access and exclusion across the city’s neighborhoods. I asked Detroiters how the internet influences their sense of belonging, daily routine, and wishes for the city. In these conversations, it became clear that they share a desire for resilient digital infrastructure that allows everyone to go online, but they sometimes have conflicting opinions about how to achieve that goal.

Based on these observations, I’m exploring how municipally subsidized community mesh networks can support new public spaces, landscape strategies, ownership models, housing types, and other urban design elements. Distinct from traditional hub-and-spoke internet networks, mesh networks connect distributed fields of routers, leveraging the bandwidths of multiple points of internet connectivity to create broad territories of wireless access. The dispersal of routers in a mesh network, often attached to residential balconies or rooftops, reveals a latent social network and, like the aforementioned parking lots, prompts us to rethink how public infrastructure can enable public assembly. More recently, I’ve been collaborating with a faith-based organization in Detroit to develop strategies that convert a church into a wi-fi access point for the community, while also affording educational and social programming.

The internet is inextricably linked to contemporary urban space. As the pandemic intensifies the demand for affordable broadband, designers must come up with more inventive ways to connect both physically and virtually, especially for lower-income BIPOC and rural communities that are most in need. As for myself, physical distancing has complicated my public engagement work—I am having to think creatively so I can hear from people unable to get online—but I’m also motivated by the current situation. We all should be.

Cyrus Peñarroyo is a partner in the Ann Arbor, Michigan–based design practice EXTENTS and teaches at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College.