In recent years, experiments in architecture have produced forms, moods, and effects that resist easy labeling. Still, some have tried putting a name to this diverse, variegated work: the “postdigital.” The term was first popularized by the British architect Sam Jacobs, who considered postdigital drawing (often taking the form of collage) to be a meaningful critique of the digital positivism that proliferated in the 2000s. The historian Mario Carpo took the opposite tack, finding the return to collage to be both anti-digital and repressed. Exploring a third way, architect Adam Fure suggested that the postdigital is, in actuality, “very digital” and all around us. For this reason, it no longer deserves its own special category.

If we accept Fure’s expansion of the term, then we see that postdigital architecture cannot be reduced to any repertoire of formal styles and techniques, but rather represents a paradigmatic condition that is inescapable. In this brave new networked world, stable identities give way to indeterminate chimeras. The New Aesthetic (TNA), a blog run by the artist-theorist James Bridle, is a running catalog of such oddities: Russian cows are outfitted with virtual reality goggles under the hypothesis that virtual blue skies and green pastures will lead to greater milk production. The Spanish fashion house Balenciaga deploys deepfake models for its latest collection launch. Smartphone cameras autocorrect the toxic orange haze from California wildfires as if in algorithmic denial of climate disaster. Like a techno-wolf in sheep’s clothing, each of these strangely alluring yet off-putting sights is instructive, teaching us to distrust outward appearances while also underscoring the fact that networked imagery and objects are engineered to manipulate us.

In a 2011 talk explaining his reasons for launching TNA, Bridle confessed to “hav[ing] no idea what anything is or what it does anymore.” Ten years on, the feeling has grown only more acute. Our sensory apparatuses are unsuited for navigating the networks in which we are enmeshed. Our attempts to make sense of conflicts—political, aesthetic, and otherwise—or to predict outcomes easily come undone. Events and situations don’t appear to add up, leading to a widespread feeling of alienation. Greater numbers of people fall back on conspiracy theories to cope.

Any sense of a fixed spatiotemporal order—that of the pre- or early industrial past—has since been decimated, terraformed by invisible infrastructures of data. The internet of things, surveillance capitalism, social media—all have flattened perceptions of the world and scrambled timelines, discourses, and feedback loops. Friends and enemies, be they human or nonhuman, take on enigmatic guises signaling certain behaviors while at the same time subverting them. No one and no thing is quite what it seems.

This networked paradigm has decoupled identities and behaviors from the qualities typically associated with them. As a result, identity itself becomes denaturalized and queered, while seemingly incompatible dispositions fold into one another. Within architecture, the old categories that long sorted disciplinary knowledge have ceased to apply. To persist, then, in drawing formalistic distinctions—postmodern collage versus digital fabrication, cartoonish millennial color palettes versus the rendered effects of subsurface scattering—is to deny the very basis of postdigital culture, i.e., the fungibility of appearances.

If the stable identities that space, time, and architecture once guaranteed now seem to elude us, then we have little choice but to recalibrate our analytical lens. By replacing space and time with new coefficients (namely, appearance and behavior) and reconceiving form as the sorting of informational ready-mades (the bizarre “creatures” that run amok on TNA and everywhere else), we can better grapple with our postdigital condition and discover the creative, liberatory potentials within.

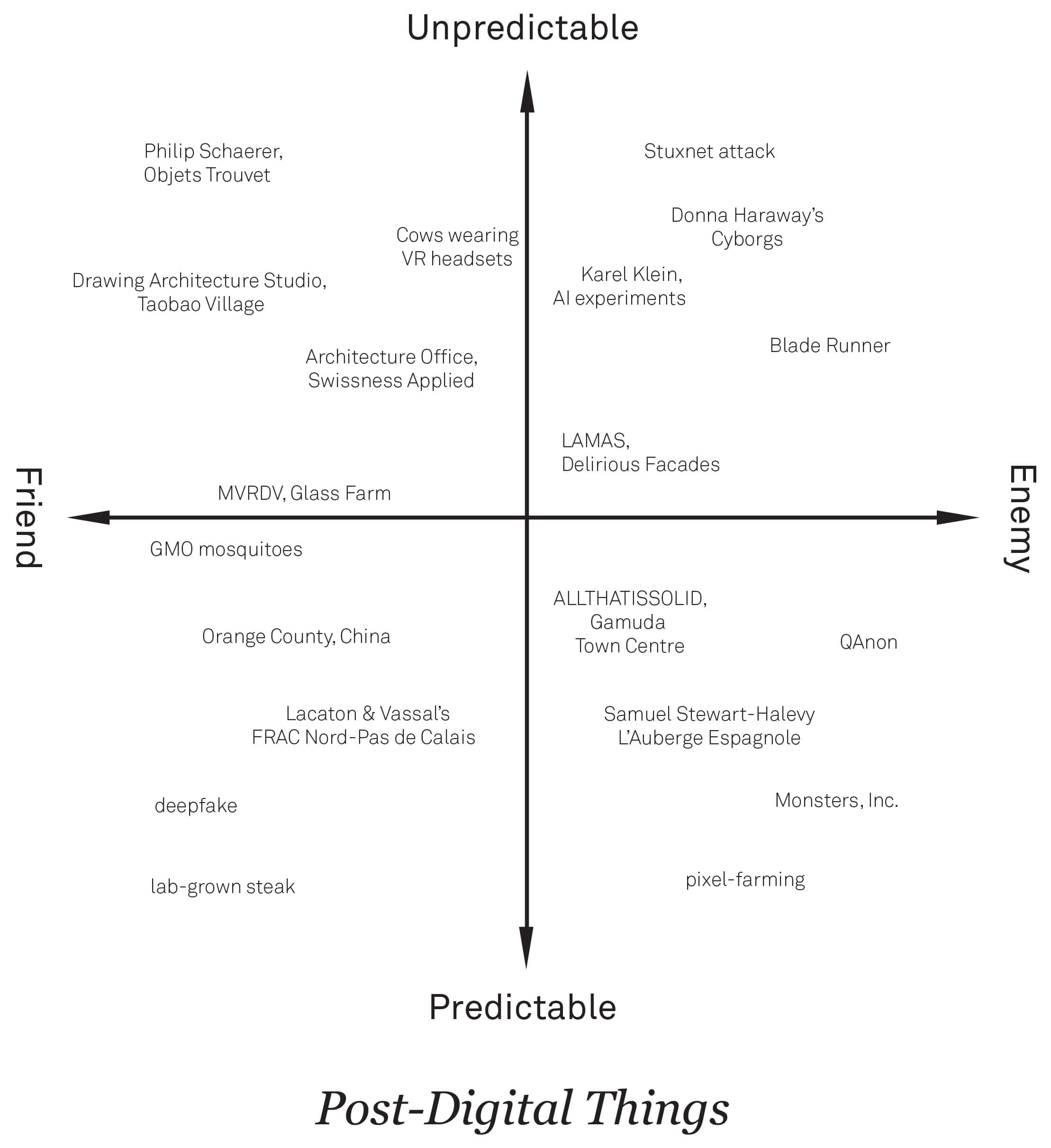

Such a framework, I propose, can be represented in two dimensions, with a horizontal axis differentiated along a friend-enemy spectrum and a vertical axis encompassing a range of predictable and unpredictable behaviors. All manner of architectural and nonarchitectural species can be kettled into these four quadrants, attesting to wide-ranging and diverse sets of contemporary phenomena with which designers can productively engage. As we plot these ostensible friends and enemies, knowns and unknowns, we discover that such distinctions blur and are taken to change, depending on the standpoint of the observer.

The right side of the matrix is where perceived enemies dwell. The unpredictable enemy (top-right quadrant) is akin to the generative adversarial network (GAN) architects and educators like SCI-Arc instructor Karel Klein are beginning to experiment with. Klein’s students generate stochastic and bestial imagery by feeding the GAN algorithm houseplants and other nonarchitectural information; what this predictive algorithm spits out is unpredictable and challenges conventional notions about what can be called architecture.

Meanwhile, the predictable enemy (bottom-right quadrant) behaves in reverse. Here we find funny, oddball creatures like those in Pixar’s Monsters, Inc., a film that normalizes outwardly monstrous appearances. My own studio, ALLTHATISSOLID, has deployed techniques of the predictable enemy in order to perform otherwise ordinary architectural duties. Working at a sprawling exurban residential development outside Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, we designed a dense, seven-acre mixed-use town center that, in keeping with the client’s wishes, simulates a Disney-like townscape worthy of Instagram. Intrigued by this surreal, fake urbanism, we tried to point up the scalar paradox at work, where tightly knit “medieval” blocks exist in the middle of nowhere. By conforming to the risk-averse predictability of real estate spreadsheets and client demands, we discovered a truly authentic expression of monstrous contradictions.

On the other side of the matrix lies the unpredictable friend (top-left quadrant), where we find the Beijing-based Drawing Architecture Studio, among others. The atelier’s magnificent, sprawling tableaux expose the infrastructures of contemporary life, but do so in beguiling ways. For instance, TaoBao Village • Smallacre City recontextualizes a Jeffersonian utopia—Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City—in 21st-century China, where rural villages have been transformed into manufacturing hubs for e-retailers. The logic is as dizzying as the panoramic drawings themselves, but by making unusual historical connections, the architects discover new urban possibilities.

Lastly, there is the predictable friend (bottom-left quadrant), the most benign-sounding of all these postdigital creatures but also the most unnerving. Here we find lab-grown meat and AI-generated deepfakes, whose fidelity to original models grows more perfect over time. Architectural copies are just as prolific: Swiss red chalet roofs sweep through Israeli settlements, while in a Beijing exurb, neo-Italianate tract homes re-create the affectations of Orange County McMansions. But “critical” copying, whereby the referent is consciously modified and acted upon, is much harder to come by.

Antagonistic algorithms, bashful monsters, Disney villages, “Orange County, China”—these are just my postdigital frenemies. Moreover, the matrix I propose merely offers one way to parse a diverse range of phenomena without recourse to conventional formal or methodological categories. In our postdigital times, the world is teeming with objects, creatures, and ready-mades that solicit our engagement. Only by becoming attuned to the malleability of appearance and behavior can we creatively intervene in systems and leverage them for maximal effects.

Max Kuo is a partner of ALLTHATISSOLID, a frequent design critic at the Harvard GSD, and currently a visiting critic at Syracuse University. His recent work explores pluralism in postdigital design culture.