Now active in over 30 countries around the world, French startup Iconem is working to preserve global architectural and urban heritage one photograph at a time. Leveraging complex modeling algorithms, drone technology, cloud computing, and, increasingly, artificial intelligence (AI), the firm has documented major sites like Palmyra and Leptis Magna, producing digital versions of at-risk sites at resolutions never seen, and sharing their many-terabyte models with researchers and with the public in the form of exhibitions, augmented reality experiences, and 1:1 projection installations across the globe. AN spoke with founder and CEO Yves Ubelmann, a trained architect, and CFO Etienne Tellier, who also works closely on exhibition development, about Iconem’s work, technology, and plans for the future.

The Architect’s Newspaper: Tell me a bit about how Iconem got started and what you do.

Yves Ubelmann: I founded Iconem six years ago. At the time I was an architect working in Afghanistan, in Pakistan, in Iran, in Syria. In the field, I was seeing the disappearance of archeological sites and I was concerned by that. I wanted to find a new way to record these sites and to preserve them even if the sites themselves might disappear in the future. The idea behind Iconem was to use new technology like drones and artificial intelligence, as well as more standard digital photography, in order to create a digital copy or model of the site along with partner researchers in these different countries.

AN: You mentioned drones and AI; what technology are you using?

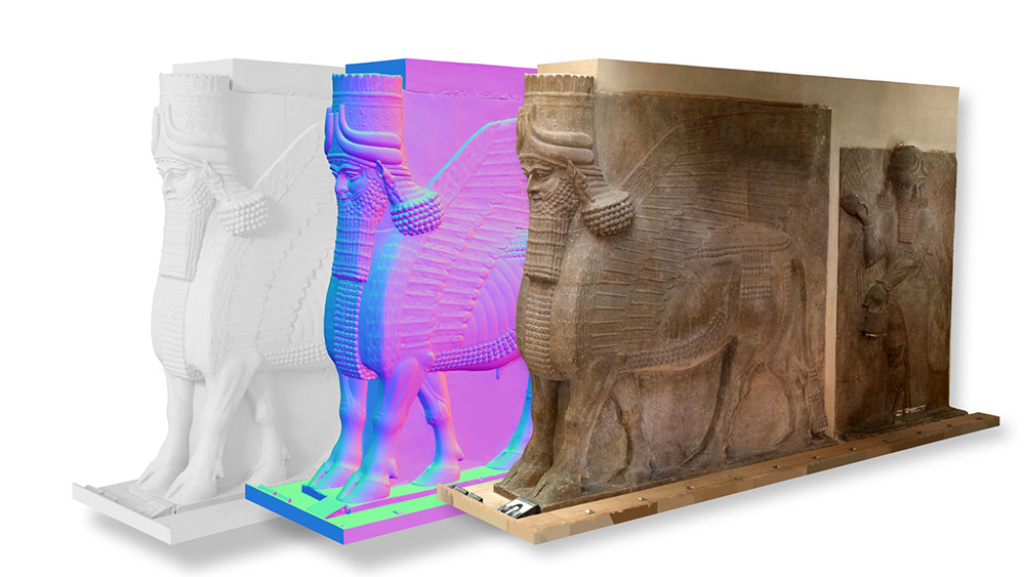

YU: We have a partnership with a lab in France, the INRIA (Institut National de Recherche en Informatique/National Institute for Research in Computer Science and Automation). They discovered an algorithm that could transform a 2D picture into a 3D point cloud, which is a projection of every pixel of the picture into space. These points in the point cloud in turn reproduce the shape and the color of the environment, the building and so on. It takes billions of points that reproduce the complexity of a place in a photorealistic manner, but because the points are so tiny and so huge a number that you cannot see the point, but you see only the shape on the building in 3D.

Etienne Tellier: The generic term for the technology that converts the big datasets of pictures into 3D models is photogrammetry.

YU: Which is just one process. Even still, photogrammetry was invented more than 100 years ago…Before it was a manual process and we were only able to reproduce just a part of the wall or something like that. Big data processing has led us to be able to reproduce a huge part of the real environment. It’s a very new way of doing things. Just in the last two years, we’ve become able to make a copy of an entire city—like Mosul or Aleppo—something not even possible before.

We also have a platform to manage this huge amount of data and we’re working with cloud computing. In the future we want to open this platform to the public.

AN: All of this technology has already grown so quickly. What do you see coming next?

YU: Drone technology is becoming more and more efficient. Drones will go farther and farther, because batteries last longer, so we can imagine documenting sites that are not accessible to us, because they’re in a rebel zone, for example.

Cameras also continue to become better and better. Today we can produce a model with one point for one millimeter and I think in the future we will be able to have ten points for one millimeter. That will enable us to see every detail of something like small writing on a stone.

ET: Another possible evolution, and we are already beginning to see this happen thanks to artificial intelligence, is automatic recognition of what is shown by a 3D model. That’s something you can already have with 2D pictures. There are algorithms that can analyze a 2D picture and say, “Oh okay, this is a cat. This is a car.” Soon there will probably also be the same thing for 3D models, where algorithms will be able to detect the architectural components and features of your 3D model and say, “Okay, this is a Corinthian column. This dates back to the second century BC.”

And one of the technologies we are working on is the technology to create beautiful images from 3D models. We’ve had difficulties to overcome because our 3D models are huge. As Yves said before, they are composed of billions of points. And for the moment there is no 3D software available on the market that makes it possible to easily manipulate a very big 3D model in order to create computer-generated videos. So what we did is we created our own tool, where we don’t have to lower the quality of our 3D models. We can keep the native resolution quality photorealism of our big 3D models, and create very beautiful videos from them that can be as big as a 32K and can be projected onto very big areas. There will be big developments in this field in the future.

AN: Speaking of projections, what are your approaches to making your research accessible? Once you’ve preserved a site, how does it become something that people can experience, whether they’re specialists or the public?

YU: There are two ways to open this data to the public. The first way is producing digital exhibitions that people can see, which we are currently doing today for many institutions all over the world. The other way is to give access directly to the raw data, from which you can take measurements or investigate a detail of architecture. This platform is open to specialists, to the scientific community, to academics.

The first exhibition we did was with the Louvre in Paris at the Grand Palais for an exhibition called Sites Éternels [Eternal Sites] where we projection mapped a huge box, 600 square meters [6,458 square feet], with 3D video. We were able to project monuments like the Damascus Mosque or Palmyra sites and the visitors are surrounded by it at a huge scale. The idea is to reproduce landscape, monuments, at scale of one to one so the visitor feels like they’re inside the sites.

AN: So you could project one to one?

ET: Yes, we can project one to one. For example, in the exhibition we participated to recently, in L’Institut du monde arabe in Paris, we presented four sites: Palmyra, Aleppo, Mosul, and Leptis Magna in Libya. And often the visitor could see the sites at a one to one scale. Leptis Magna was quite spectacular because people could see the columns at their exact size. It really increased the impact and emotional effect of the exhibition.

All of this is very interesting from a cultural standpoint because you can create immersive experiences where the viewer can travel through a whole city. And they can discover not only the city as a whole but also the monuments and the architectural details. They can switch between different scales—the macro scale of a city; the more micro one of the monument; and then the very micro one of a detail—seamlessly.

AN: What are you working on now?

ET: Recently, we participated in an exhibition that was financed by Microsoft that was held in Paris, at the Musée des Plans-Reliefs, a museum that has replicas of the most important sites in France. They’re 3D architectural replicas or maquettes that can be 3 meter [apx. 10 feet] wide that were commissioned by Louis XIV and created during the 17th century because he wanted to have replicas to prepare a defense in case of an invasion. Recently, Microsoft wanted to create an exhibition using augmented reality and they proposed making an experience in this museum in Paris, focusing on the replicas of Mont-Saint-Michel, the famous site in France.

We 3D scanned this replica of Mont-Saint-Michel, and also 3D scanned the actual Mont-Saint-Michel, to create an augmented reality experience in partnership with another French startup. We made very precise 3D models of both sites—the replica and the real site—and used the 3D models to create the holograms that were embedded and superimposed. Through headsets visitors would see a hologram of water going up and surrounding the replica of Mont-Saint-Michel. You could see the digital and the physical, the interplay between the two. And you could also see the site as it was hundreds of years before. It was a whole new experience relying on augmented reality and we were really happy to take part in this experience. This exhibition should travel to Seattle soon.