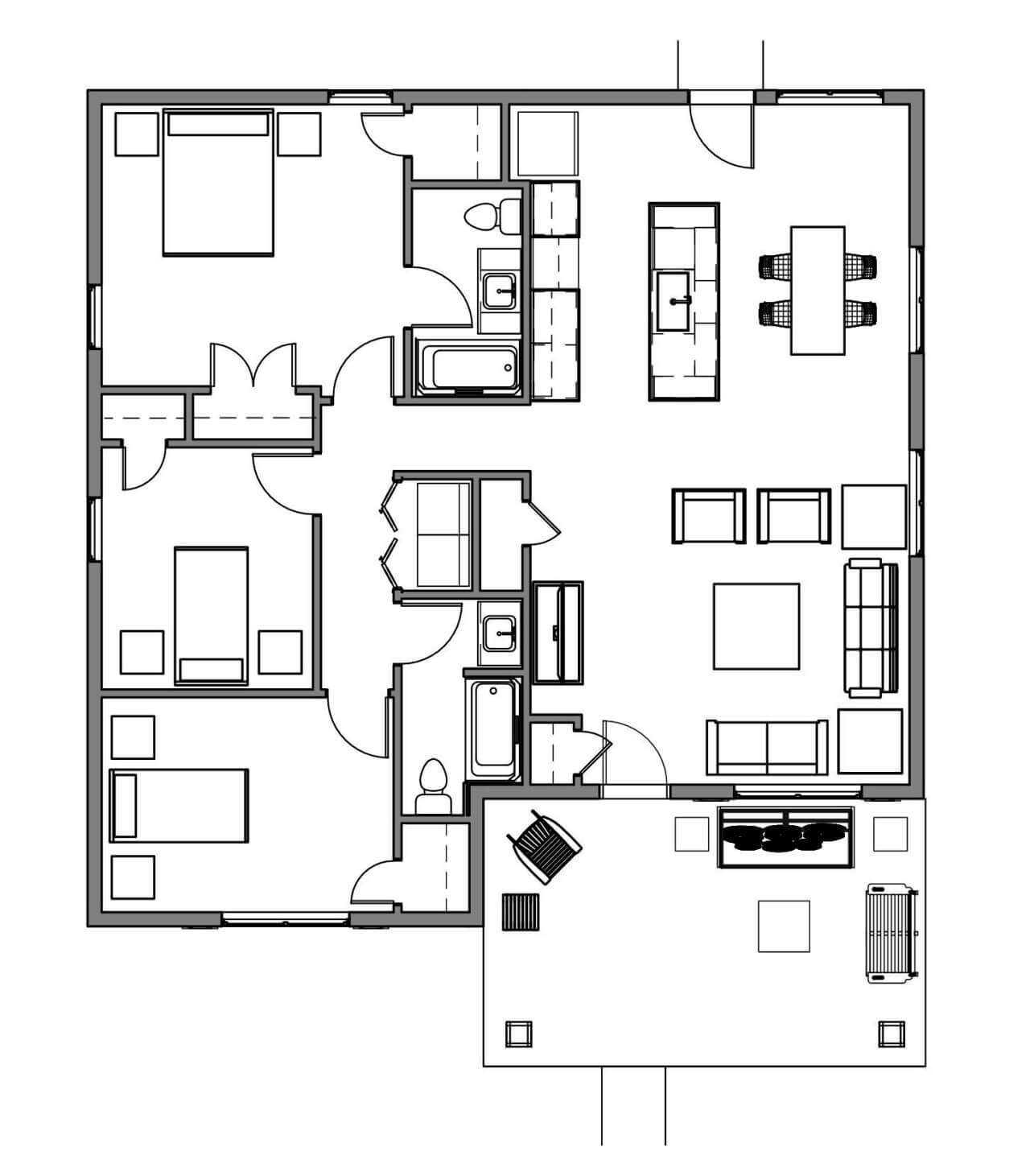

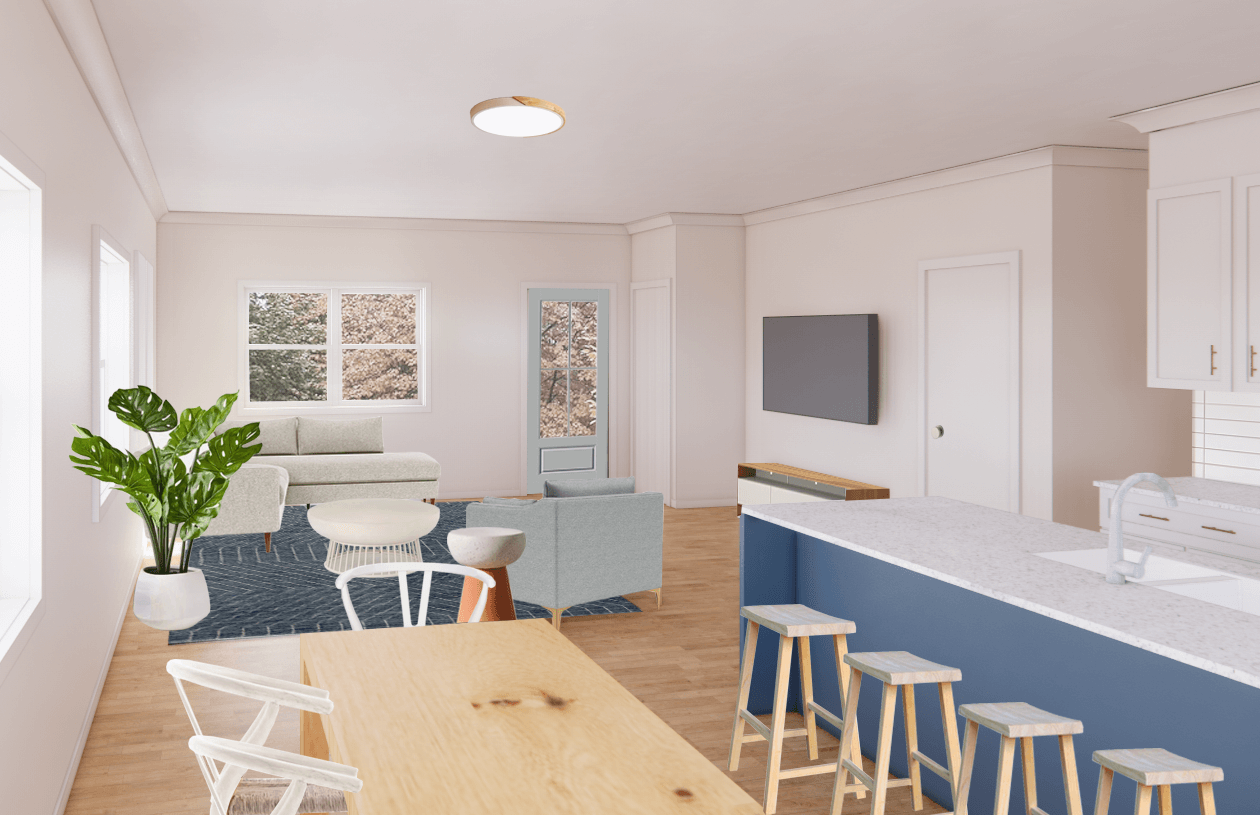

Additive construction company Alquist and the Virginia Center for Housing Research (VCHR) at Virginia Tech have partnered to design, build, and study a 3D-printed single-family home that’s the first of its kind in the United States: funded by a private-public partnership grant. Work on the three-bedroom, 1,550-square-foot home broke ground earlier this week at 217 Carnation Street in Richmond’s Midlothian neighborhood. The low-slung, bungalow-style home, which greets the street with a swing-equipped covered front porch and decorative gable wall elements, is slated for completion in October.

The grant is a $500,000 Innovation Demonstration Grant from Virginia Housing (formerly the Virginia Housing Development Authority), a nearly 50-year-old quasi-governmental organization dedicated to helping Virginia residents secure affordable housing through a range of programs. The grant enabled Alquist to purchase a modular 3D printer, the mighty BOD2, from Danish 3D printer powerhouse COBOD. Per a press release announcing the home’s groundbreaking, the gantry-type BOD2 system can be assembled—or dissembled—within a few hours and requires just two trained construction workers to be present on-site to operate. While the Richmond prototype home will be constructed with a concrete mix, the open-source nature of the system means that other, more sustainable materials can be potentially used down the line. For the Richmond project, Alquist—a company with a name that begs for further rumination—will print just the exterior walls, although both exterior and interior walls will be 3D printed in future builds.

As noted by Alquist, preliminary estimates show that the use of concrete will provide initial savings of up to 15 percent-per-square-foot of building compared with stick-built new homes, which have seen construction prices soar during the pandemic due to the explosive costs of lumber. The inherent speed and efficiency of 3D-printed homebuilding technology further drive down construction costs: With the BOD2 printer, a home’s frame can be constructed with a two-person crew in an ultra-fast 12-to-15 hours, shaving down the construction time by roughly a month. Long-term savings included decreased heating and cooling costs due to the thermal properties of concrete.

Like other 3D printing construction companies, these savings are core to Alquist’s mission. While the inaugural Richmond project isn’t a rural one, the company is particularly keen on bringing low-cost and resilient 3D-printed homes to rural communities across the U.S. While 3D-printed homes and other buildings have been piloted and built in rural and developing areas outside of the U.S. from Mexico to Malawi, this isn’t the case stateside. Alquist hopes to buck this trend as the rural housing crisis deepens due in part to “exurban migration away from the coasts accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic.” Beyond Richmond, Alquis is working with partner company Atlas Community Studios and has projects planned for rural communities in Arkansas, California, Iowa, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, North Dakota, and more. The target cost of future Alquist-constructed homes is $181,000 (with a sale price in the ballpark of $210,000), although the construction price tag and sale price of the inaugural 3D-printed home in Richmond will be higher.

“While most 3D printing endeavors focus on urban residential areas and commercial buildings, many of the regions facing the biggest housing challenges exist in rural America,” said Zachary Mannheimer, founder and CEO of Alquist, in a statement. “That’s why we partnered with Virginia Housing and Virginia Tech to build homes for people who live outside of the places where most funding for housing programs is spent.”

As for Virginia Tech’s role, the school has developed a proprietary Raspberry Pi-based smart home monitoring system that will be found in all Alquist-built dwellings. The systems include indoor environment sensing (air quality, temperature, humidity, lighting, sound, and on), a security and alarm system, emergency management including smoke and fire detection, energy consumption optimization, and more.

“The long- and short-term cost and time savings over ‘standard built’ houses continued to reveal themselves throughout the design-build process, and we are excited to pass those savings along to the family that eventually calls this amazing project ‘home,’” said Dr. Andrew McCoy, Alquist’s Virginia Tech lead who serves as director of the VCHR and associate director of the Myers-Lawson School of Construction, where is also a professor of Building Construction.

In addition to Virginia Teach and Virginia Housing, additional project partners for the 3D-printed home at 217 Carnation Street include general contractor RMT Construction & Development Group and Richmond-based nonprofits Project: HOMES and the Better Housing Coalition, which will together provide project site and homeownership services along with regulatory compliance guidance including permitting, zoning, and insurance.