When I visited Arup’s New York offices, I was taken from the sunlit open areas on the fifth floor, down some stairs, through dark corridors, and into a windowless room with painted dark walls. There was a projector screen, someone by a computer, and a person in all black sitting off to the side. In the center of the room was a black leather swivel chair, semi-orb shaped and raised high. I was invited to sit. I said that the whole thing felt ominous, like I was being interrogated, but given that I was the interrogator in this situation, maybe it should’ve felt more like I was some B-movie villain, looking over some empire through digital screens.

But this was no evil lair—this room was Arup’s SoundLab, one of many across the firm’s global offices, each varying in design but all with identical sound systems and sonic experiences. “Basically, you are currently sat in a room that uses what’s known as an Ambisonic sound system,” explained Raj Patel, the person in all black and a global leader of acoustics. “What the Ambisonic sound system does is it allows you to simulate sound in three dimensions. There’s also a measurement technique that allows you to go and measure an existing space, capture its acoustics in three dimensions, and play it back here.”

It was in rooms like these that experiments were done to create a new sort of architectonic instrument in the form of a reverberation chamber for none other than Icelandic superstar Björk. “[Björk] often described two different voices that she uses for singing,” explained Arup associate and acoustic designer Shane Myrbeck, who had Skyped in from San Francisco to join the meeting. “One is the one she uses on stage, that’s through the microphone, through the PA, and that’s a specific emotion for her. And then there’s the other voice that she uses when she’s singing by herself or in a nice acoustic room.” She wanted to bring this latter experience to the stages she’ll be performing at as she travels on her Cornucopia tour, which is organized a bit like a series of theatrical residencies and began with sold-out shows at The Shed earlier this May.

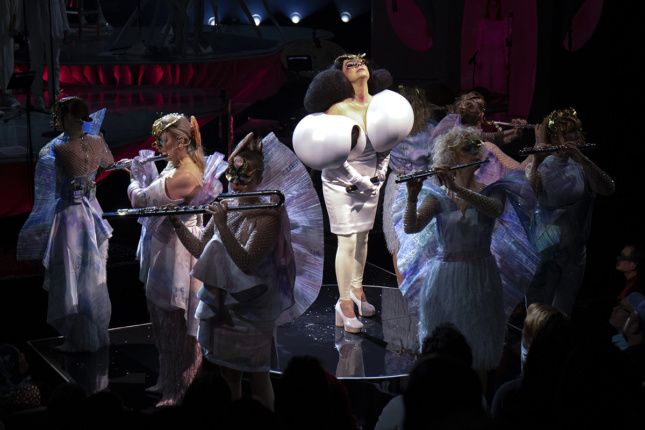

Many musicians accompany Björk, with the flutists sometimes joining her within the compact chamber. (Santiago Felipe/Courtesy Björk and Arup)

While Arup and Björk had been in conversation at multiple points over the past few years, the reverberation chamber was imagined just last year and was designed and built in under six months. “She was very focused on it sounding right first,” Myrbeck recounted. “We often work with architects, so there’s a form to study or a palette of forms to study. In this case, our initial question, was ‘Okay, what do you want it to look like?’ And she was like, ‘Don’t think of it that way. It needs to sound good first.’”

Myrbeck said, “She wanted it to be as reverberant as possible…We kept using words like chapel or alluding to the cathedral-type sound.” However, cathedrals derive their distinctive sound in large part from their sheer volume, something that obviously couldn’t easily be toured across the world and mounted on any given stage. Still, “there are some precedents out there in the world,” explained Myrbeck. “Before they had digital reverbs, they would literally just have these concrete rooms in the basement and put a loudspeaker down there and just send the sound down to these chambers and record that. That was the old reverb effect. And those are pretty small rooms.”

Another reference was the large-scale sculpture Tvísöngur, located on Iceland’s east coast. Opened in 2012 and designed by the German artist Lukas Kühne, the installation comprises five large concrete domes that echo the incoming wind at various harmonies.

However, both of these examples were made of concrete, an unrealistic material to make a relatively large, but still easily transportable, chamber for stage out of. “[The reverberation chamber] needed to be something that she could tour with,” said Myrbeck. “A lot of the simulations that we did were materials studies.” The team used Rhino models with acoustic software that simulated the known resonances, derived from nearly a century’s worth of data, of different materials, like concrete, acrylic, plaster, and others. Inside these simulated environments the team at Arup used a sample of an isolated vocal track Björk had recorded for them and sent her the various ways it would sound in spaces of various materials and shapes, which she listened to on headphones in her own studio, and later, in a SoundLab.

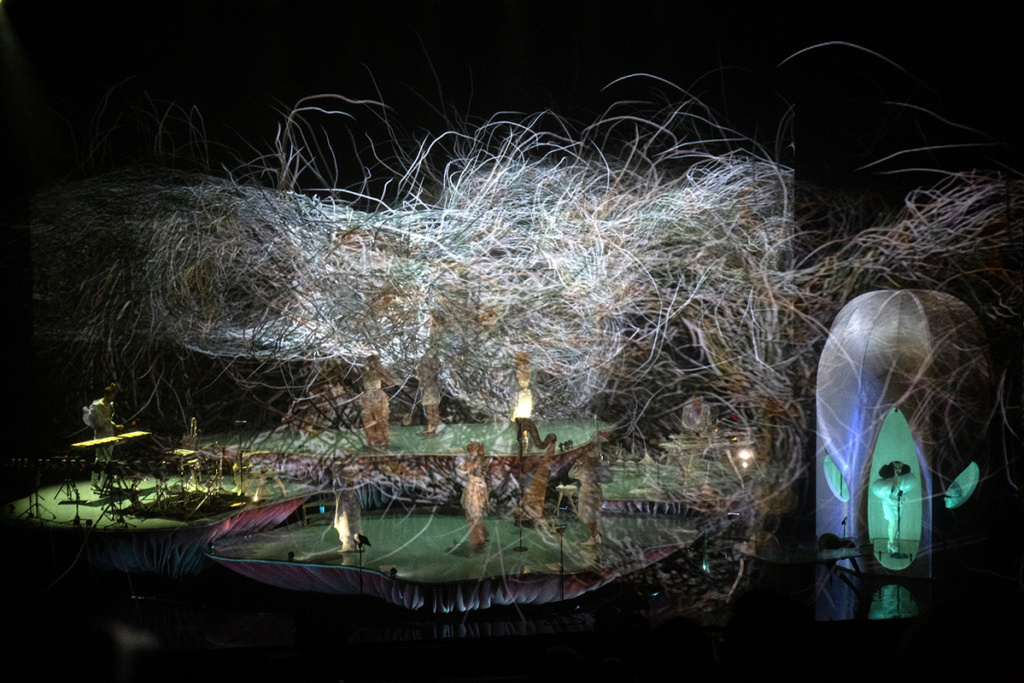

The elaborate sets—including the reverberation chamber—have to be transportable throughout the tour. (Santiago Felipe/Courtesy Björk and Arup)

“One of the other things about a small room is that, just due to the size of acoustic waves, you get these very specific resonances in different places,” Myrbeck said. He compared it to the weird sonic effects of singing in your shower. In rooms like the SoundLab, where we met, one of the central design challenges is to minimize those effects in order to create a sort of neutral room that can simulate any space—whether an amphitheater, a train hall, or a small lobby. In the case of designing Björk’s reverberation chamber, “it was just about embracing [those resonances] and trying to make them as evocative as possible so that Björk could experiment with those different resonances in the different places that she could stand in the chamber.” Rather than eliminating all this sonic unevenness, the goal was to give the singer the power to “activate” it.

In the end, Arup and Björk decided on an 16.4-foot-high, just-under 10-foot-wide octagonal structure with flat sides and a vaulted roof of molded plywood. There is one central microphone, while a few others are placed around the top perimeter. The design is modular and can easily be dis- and re-assembled. It also uses common materials: plywood and a plaster composite, about an inch thick, that has a similar density and resonance quality to concrete. These are materials that are easy to repair on the fly (while the roof is molded, the walls are just standard plywood sheets). The automated door and the transparent cutaways are acrylic, about an inch thick, while the floor is plywood and is slightly elevated so that it has its own resonant properties. The reverberation chamber has simple bolted connections that allow it to “be as airtight as possible while still allowing her to breathe freely,” protecting it against acoustic leakage.

Björk will even invite inside the shows’ flutists, whose own bodies reshape the resonant qualities of the compact chamber. “It’s very much an instrument,” Myrbeck said, and serves as a way to literalize emotional shifts in the performance.

“I think that one of the exciting things about the design process [with Björk] was her really sophisticated blend of the acoustic and natural and almost ancient tradition—there’s not much more ancient than singing; it’s one of the oldest forms of expression—and her embracing of the very futuristic, state-of-the-art digital technology,” said Myrbeck. “The design process expressed that as well.”

For more on the latest in AEC technology and for information about the upcoming TECH+ conference, visit techplusexpo.com/nyc/.