3-D printing in architecture is growing—literally. Once limited to models and small pieces, the technology has recently been adapted to large-scale projects, like the world’s largest 3-D-printed concrete bridge in Shanghai, a stainless steel bridge in the Netherlands, and walls for U.S. military barracks. An Austin-based company has even begun selling plans for 3-D-printed houses, though thus far it seems like none have been built.

However, as first reported in 2016, Branch Technology, is set to build what it claims is the “world’s first freeform 3-D-printed house.” The firm has already fabricated an array of projects with its giant 3-D printing armature: furniture, drone landing pads, an award-winning pavilion made in collaboration with SHoP architects for Design Miami in 2016, and what the company claims is the world’s largest 3-D-printed structure. However, this would be the first building to be entirely made with the company’s printing tech.

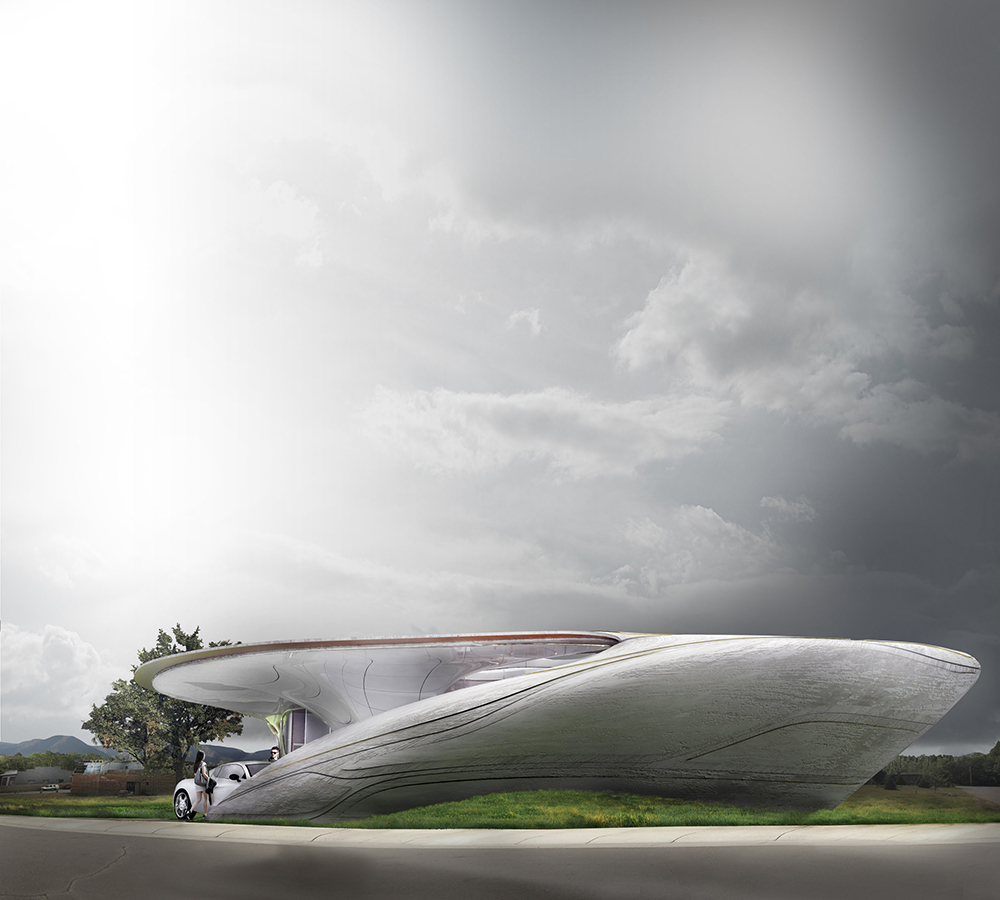

The project got its start in 2016, when Branch Technology hosted its Freeform Home Design Challenge, inviting firms from around the world to propose a home to be made with its cellular fabrication technology. Out of the nearly 1,300 registrants, the winning entry, called Curve Appeal, came from WATG, and will be completed in partnership with various other firms and labs.

The home, which has been designed with attention to the natural light available on the lot in Chattanooga, Tennessee, is intended to be net zero energy. It’s being built out of around 100 pieces of printed carbon-fiber-reinforced ABS thermoplastic, five-pound beams of which have been shown to bear as much as 3,600 pounds. Branch has been testing individual components and structural models, and creep testing the entire system to ensure that every part of the home comes together safely and securely.

According to Branch’s David Goodloe, combining lightness with structural integrity defines the firm’s work, making its technology “fundamentally different” than other 3-D-printing construction companies.

“Instead of asking ‘How much can we 3-D print?'” Goodloe said, “we are asking ‘how little?’” Rather than trying to make components wholly of plastic or another printed material, Branch is leveraging freeform printing to produce what it refers to as a matrix, a lattice-like structure, that supports other materials. The printed form creates the structure to which materials like gypsum composite can be added to increase structural capacity, insulation, and energy efficiency.

To build bigger, Branch has been scaling up. The company has recently doubled its capacity with four new printers, and is building a new factory to incorporate its advances in automation and speed. The goal, as with many firms and labs experimenting with 3-D printing in architecture and construction, is to bring greater customization to construction. Branch is aiming to complete its home later this year.