The theme of this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, still on track to open on May 22, asks attendees and observers, How will we live together? For Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), that answer appears to be “on the moon,” as the multinational design juggernaut will bring its Moon Village to Venice’s Arsenale.

For the Life Beyond Earth exhibition, SOM and the European Space Agency (continuing a partnership launched in 2018), will put both renderings and architectural models from the Moon Village on display. Life Beyond Earth rightfully interrogates the multidisciplinary approaches towards technology, planning, architecture, material and rocket science, robotics, and psychology needed to realize a fully functional off-world settlement. Of course, much as technologies first discovered by NASA for space missions trickled into mainstream adoption (including GPS, cordless power tools, and satellite imagery), Life Beyond Earth will also demonstrate how the cohabitation and resource use strategies of the Moon Village can be applied terrestrially. SOM is responsible for master planning, designing, and engineering the project.

First revealed in 2019 as a permanent launching point for extraterrestrial exploration in 2050 and beyond, the Moon Village was conceived as a self-sustaining, long-term lunar outpost along the rim of Shackleton Crater on the Moon’s south pole. The site receives nearly continuous sunlight for most of the lunar year, creating an opportunity to harvest solar power, while the shadowed interior of the crater could potentially hold water ice for consumption (and combining the two could theoretically produce hydrogen rocket fuel), for what SOM and the ESA call “in situ resource utilization.”

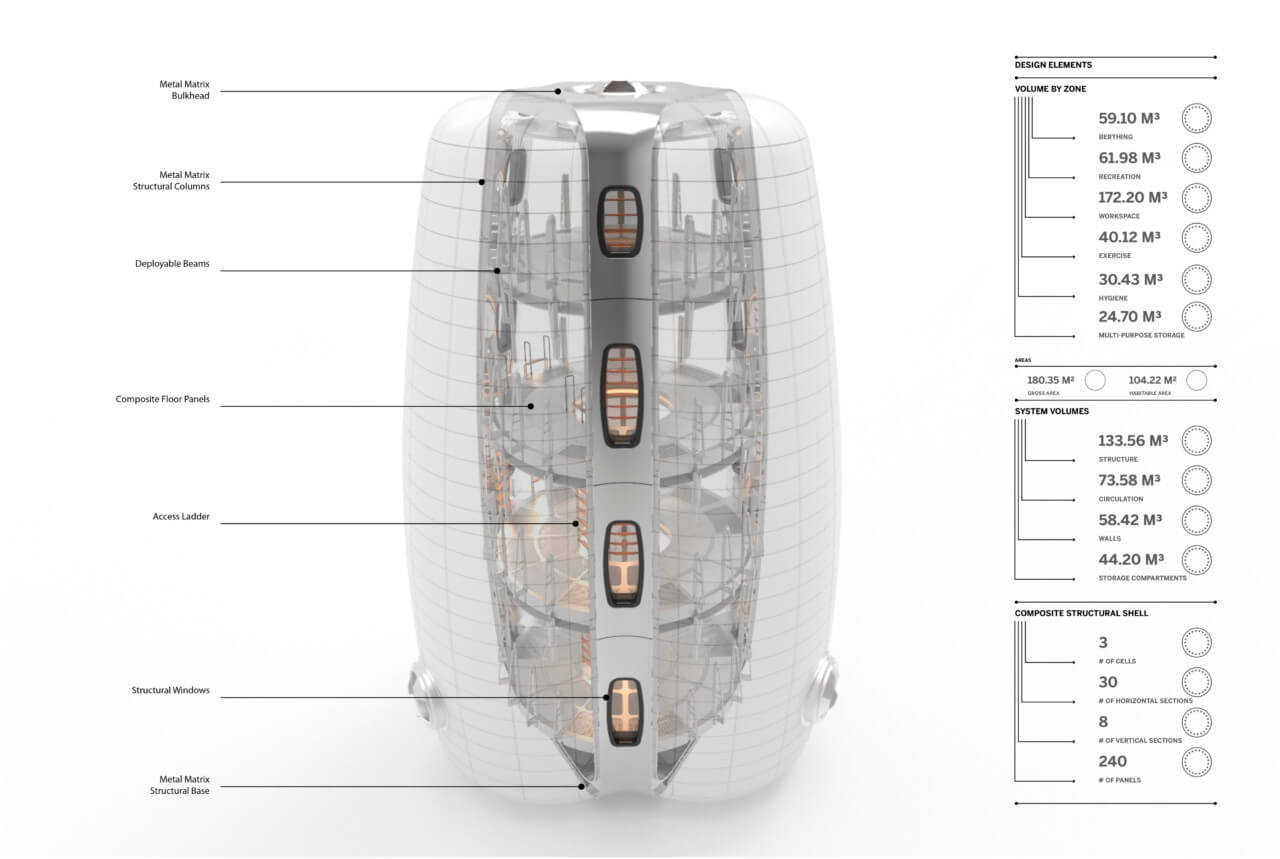

SOM has envisioned multistory cylindrical habitat clusters linked via pressurized paths amid fields of solar collectors, and Life Beyond Earth will feature a larger-scale model of one of the vertical modules. Each, at full size, would be approximately 13,772 cubic feet with about 1,119 square feet of usable space within for four-to-six occupants. Rather than exclusively 3D printing each living module from materials sourced in-situ to start with (as NASA has chosen to focus on for their Mars habitats), each habitat would feature a rigid metal frame filled with a durable inflatable outer shell, with windows punched into vertical external framing strips. Eventually, shells 3D-printed from local regolith could protect the modules from radiation, fluctuations in temperature, and dust, greatly extending the life of each structure.

Life Beyond Earth will be staged for the duration of the 17th Architecture Biennale in the Corderie, a former production hub of pre-industrial Venice that now closely resembles a more modern warehouse; the contrast between potential high-tech futures and exposed concrete, brick, and timber is a stark one. The exhibition will also supplement the habitat models with digital animations and static renderings, portraying an aspirational, technological future within our grasp.