Forensic Architecture has garnered a significant reputation within the field of architecture (they had a major showing at the most recent Chicago Architecture Biennial) and beyond for their work reconstructing violent events perpetrated by state actors and others using architectural tools and emerging technologies. The collective’s work has been displayed everywhere from the courthouse to major art exhibitions, including during this past year’s Whitney Biennial. The video One Building, One Bomb, co-produced with The New York Times, won an Emmy this past year, and in 2018 they were also nominated for the United Kingdom’s prestigious Turner Prize.

This month, Forensic Architecture, which is based out of Goldsmiths, University of London, will have its first major U.S. survey; Forensic Architecture: True to Scale will open on February 20 at the Museum of Art and Design at Miami Dade College. Ahead of the Miami exhibition, TECH+ spoke with Forensic Architecture founder Eyal Weizman to discuss the changes of the past decade, the power of technology, and the importance of forensics in a “post-truth” era.

Drew Zeiba: Forensic architecture began a decade ago. How has the project changed and how have the tools you use evolved since then?

Eyal Weizman: When we started around 2010, it was the beginning of the Arab Spring and the really heartbreaking civil war that came in its wake. Those particular sets of conflicts had a particular texture to them. They happened in an environment that had a lot of mobile phones and in the areas where there’s internet connectivity, and where the government’s ability to shut down the internet was not always successful. We started being in an environment where increasingly you had more and more videos around incidents that we could map. It was also the early teens where at the time, in London great protest around tuition fees and then the big protest after the police killing of Mark Duggan in North London. This killing was during a period when police did not yet have dash cams. And ever since, we’ve seen the introduction of body cams and dash cams to police investigations.

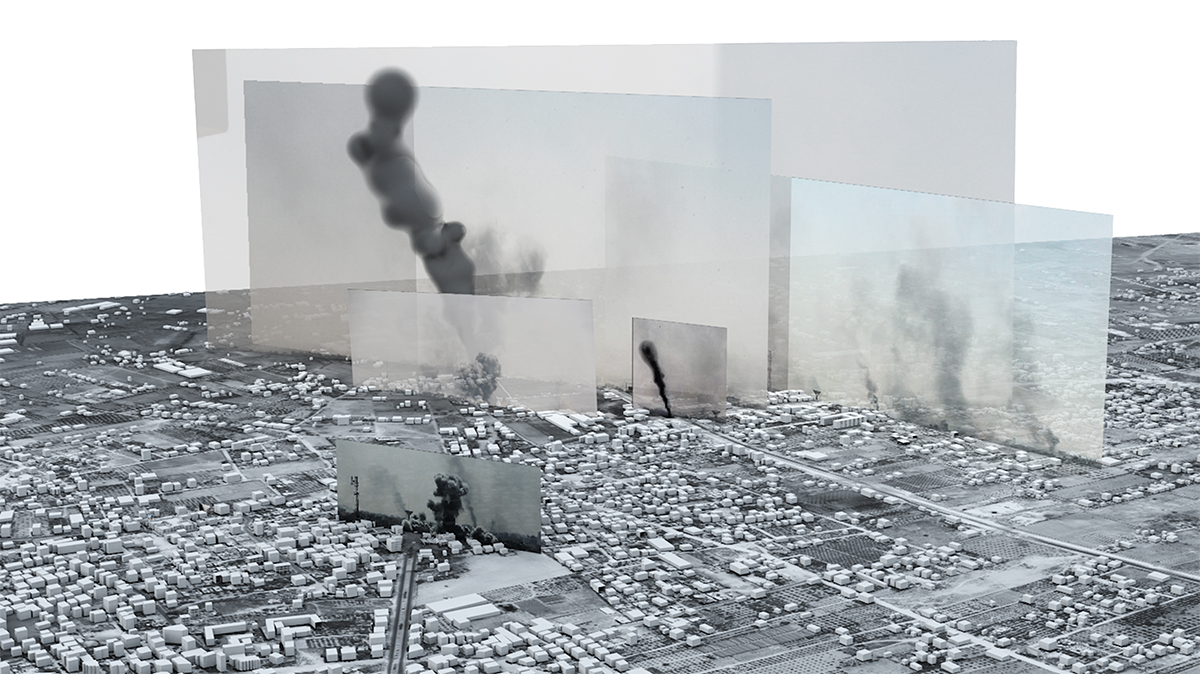

If you look today at the conflicts that are taking place, we have several thousand videos, hours long, broadcasting live as things are happening. The sheer media density requires us to use different technologies in order to bring accountability. We have recently developed machine vision and machine learning technologies that, working together with human researcher, can speed up the process of sieving through thousands and thousands and thousands of hours of content coming from confrontations with policing Hong Kong, for example. In relation to police violence, we have now concluded the investigation in Chicago [into the police killing of Harith Augustus] with full body cams available, several dash cams, a CCTV, etc.

We are working in a much more media-saturated environment and need new tools like artificial intelligence to help us identify materials like our work on Warren Kanders that used machine learning. [Kanders is the ousted vice chairman of the board of the Whitney Museum, whose company Safariland sells tear gas used at the U.S.-Mexico border, in Gaza, and elsewhere, including in U.S. cities such as Baltimore and Ferguson, Missouri.] We’re creating virtual reality sites for witnesses to walk through the scene of the together with the psychologists and lawyer and protection, but can also recall events. And we are trying to be at cutting edge of technologies that would help social movements and civil society to invert the balance of epistemological power, against the monopoly of knowledge that states have over information in battlefields and in crime scenes.

The abundance of images also has to do with the increasing presence of surveillance—including by CCTV cameras and police body cams, as you mention. How can architectural and technological tools invert the power relationship embedded in some of these commonplace image-making tools?

Forensics have to be in the hands of the people. Forensics was developed as a state tools, as a form of state power, as a police tool. But when the police is the agency that dispenses violence and the agency that’s investigating it, we have a problem. We absolutely need to be able to have independent groups holding police to account. And what we have is our creativity and we can effectively mobilize and make more of much fewer bits of data and image, because we’re working aesthetically and we work socially with those independent groups in producing evidence. We socialize the production of evidence, we make it a collective social practice that involves the communities that are experiencing state violence continuously.

At the same time, Forensic Architecture often works in places where there is seemingly a limited amount of the evidence or data that investigators typically rely upon, or with evidence that is biased. Police body cams show the officer’s perspective only, for example. Your work is coming at a time that people are describing as “post-truth.” How does the work of Forensic Architecture fit in to this political context?

The very nature of what we call investigative aesthetics is based on working with weak signals and with partial data. You need to fill that gap with a relation between those points you have, sort of like stars in a dark sky. You see very few dots and we need to actually see how they can support the probability of something to have occurred. And any investigative work that comes from the point of view of civil society is both about demolishing and building. So we need to use our training as critical scholars in deconstructing police statements, or military statements taken by secret services or the government—and we need to take those ruins, those scattered bits of media flotsam that exist and build something else with it.

There’s always demolition and rebuilding that takes place. That is very structural to our work. Right now, the mistrust in public institutions in the political sphere, In the so-called post-truth era, that trust is not being replaced. Those that tell us not to believe anymore in science and in think tanks and in experts are not building a new epistemology in its stead. They’re simply demolishing it. Rhetoric replaces verification. What we do similarly to them is we are questioning state given truths. We are attacking those temples of power and knowledge, but we attempt to replace them with a much more imminent form of evidence production that socializes the production of that evidence.